When Glen Rodriquez, senior manager for quality assurance at Bell Helicopter, reviewed a matrix showing the ages of his nondestructive inspectors (NDIs), he knew he had – or would eventually have – a problem.

“I saw that in the next three to five years we would lose a lot of people,” he said, “and there’s no way we could keep up.”

What he needed was a program to train new technicians in nondestructive technology – methods of measuring the structural integrity of a material, component or system without destroying it in the process. He knew Tarrant County College was just the place for such a program. After all, he had graduated from the NDT program at TCC South in the late 1980s just before it closed.

What he needed was a program to train new technicians in nondestructive technology – methods of measuring the structural integrity of a material, component or system without destroying it in the process. He knew Tarrant County College was just the place for such a program. After all, he had graduated from the NDT program at TCC South in the late 1980s just before it closed.

After some research, he made a pitch to Clint Grant, dean of TCC Northwest’s Aviation, Business and Logistics Division. “He said there’s nobody in North Texas doing this,” Grant said, “and that the various industries using NDT are starting to get concerned about it.”

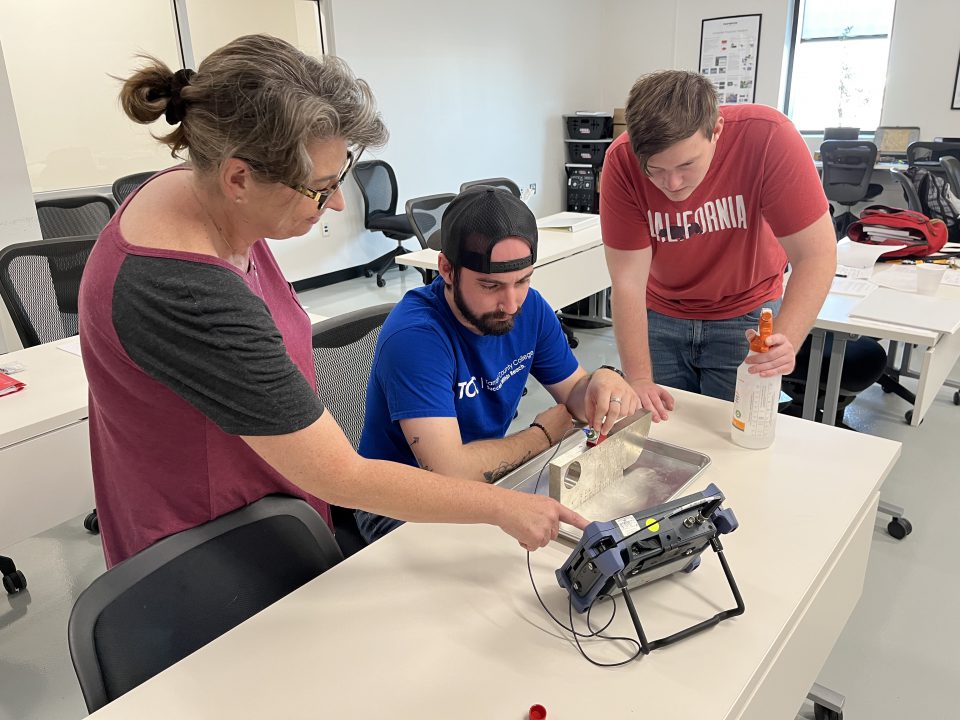

Intrigued, Grant did some research on his own, sounding out officials at such firms as Bell, Apex Aerospace, Falcon Aerospace and Lockheed Martin and putting together an exploratory committee to identify elements of a curriculum and its student outcomes. He gained approval for the program – whose formal name is Nondestructive Inspection, Testing and Evaluation – built a new lab at TCC’s Alliance Airport facility and hired a faculty member. Then COVID hit.

“We had to cancel classes and go into a pause mode because we can’t do this online,” Grant said. “The faculty member got offered a job in North Carolina and left. It was kind of a mess, so we had to wait.”

When the pandemic waned, Grant was able to proceed, enlisting the help of his Advisory Committee, chaired by Rodriquez, to help find a faculty member. One name – Venicia Queen – kept popping up, and when he attended a dinner meeting of the local chapter of the American Society of Nondestructive Testing he found Queen, probably not accidentally, sitting across from him. She applied, outshined the other finalists for the position, and began teaching this spring.

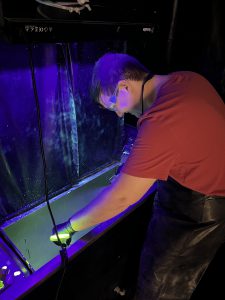

NDT is a family affair for Queen, whose father, husband and two sons are also are in the field. She began when 12 years old, helping her father test oil field equipment. “I’d go out and work with him,” she said, “holding the blacklight, recording the readings, however it worked out.” She eventually went to work for her father’s company, learning the various techniques of NDT and gaining certification through the National Aerospace Standard (NAS) testing process.

There are five primary testing methods in NDT: magnetic particle, liquid penetrant, radiographic, ultrasonic and eddy current. Queen has achieved Level III certification in each. But, although her NDT training was not through a college, she thought a degree would be helpful so she earned one in a subject she said she loved – theology.

Since NDT is highly technical, she said, most people associate it with STEM – science, technology, engineering, mathematics. “STEM is good,” she said, “but those students have a knack for college. My students don’t much like the college aspect. They want to get hands-on. They want to get dirty.”

That’s a pretty fair description of Andrew Wagner, one of the seven students in Queen’s inaugural semester. He first attended TCC right out of high school and “just didn’t know what I wanted to do – taking classes with no real goal in mind. So, I ended up eventually dropping out.”

Late in 2021, however, he heard about the NDT program through an academic adviseor at Northwest who remembered him and thought it might be a good fit. He contacted Queen, took a tour of the Alliance lab and took the plunge.

“I think it’s fantastic,” he said. “I’m more drawn to the kind of work you get to do with your hands, and this is pretty much all hands-on work. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed it so far, and Mrs. Queen has been fantastic. If I don’t understand something properly, she’ll take a second aside to help me fully understand before we move on.”

Another plus is that it comes at an affordable cost. Queen said the two courses she taught this spring – magnetic particle and liquid penetrant – carry a combined tuition of less than $400. In the private sector, she said, the cost would be about $3,200 for each course.

The two-year program leads to an Associate in Applied Science degree and prepares graduates for the certification testing process managed through their employers. Passing the tests, however, is only part of the certification process.

“The tough part of NDT is that once you get your classes and everything done, you have to have, like, 800 hours of on-job training,” Rodriquez said, but he’s working on a way to take care of that up front through paid internships with Bell Helicopter. These internships would be open to every NDT student from the time they enter TCC’s program.

Graduates entering the field will find the work and methodologies are highly varied. “It (NDT) is everywhere,” Queen said. “It’s in aircraft, amusement rides, submarines and navy vessels, oil fields and, underwater. It’s not really a consumer thing, but more industrial manufacturing. But I’ve done testing on race cars, wind turbines – you name it.

“The work is hands-on. The work is dirty. But it’s so varied and, really, the opportunities are endless.”

Just what Wagner and his classmates are looking for.