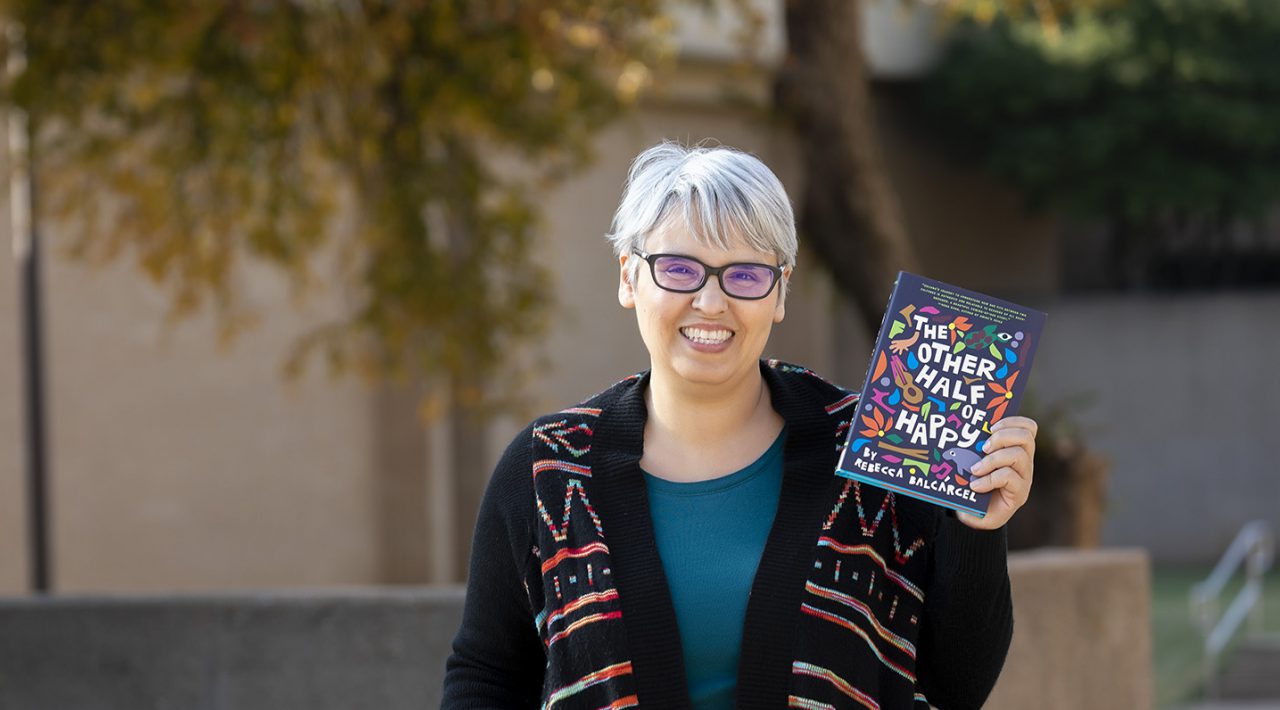

Newly published author Rebecca Balcarcel traces her love for writing to a seventh-grade writing assignment. As a 12-year-old, she struggled with many of the bi-cultural challenges faced by Quijana, the main character in her first novel, The Other Half of Happy.

“I found myself falling in love with writing when a short story was assigned for school. I started dreaming of writing a ‘real book’ then,” said Balcarcel, an associate English professor at TCC Northeast. “However, I didn’t take my writing seriously until I took a TCC Northeast Creative Writing class. I now teach that class.”

Quijana’s family mirrors her own family, said Balcarcel, whose father is Guatemalan and whose mother was born in Iowa to a family of British descent. Her character’s name is drawn from Don Quixote’s real name – Alonso Quixana – sometimes spelled Quijana, Balcarcel explained.

“Since my character wants to make a difference in the world, too, I thought the name appropriate. She does have that quixotic idealism, but she also has a practical streak from her mother’s side,” Balcarcel said, adding that the young girl often struggles with her name as the two sides fight within her.

She decided Quijana’s age should be 12 because that often is when children begin to realize how large the world is. “We are searching for our place in it. We also take on a new role in the family as we move from being the dependent child to becoming an independent person,” Balcarcel said. “We discover that we might disagree with our parents about who we are and who we can be, while at the same time needing love and support. It’s a psychologically rich time of time life, perfect for a book!”

Balcarcel will discuss her work on Wednesday, Nov. 13, at 12:30 p.m. and will host a reading interspersed with anecdotes at 6:30 p.m. both at the J. Ardis Bell Library at TCC Northeast, 828 Harwood Road, Hurst, 76054.

In December, Balcarcel will have a book signing at the Barnes and Noble in Northeast Mall in Hurst on Saturday, Dec. 7, from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m.

“This book started one summer when my grandparents from Guatemala visited (nearly 40 years ago) and I couldn’t talk to them. My lack of Spanish meant that I couldn’t truly know them, and they couldn’t truly know me. Moments like that provided material that eventually turned into the book,” she said.

About six years ago, Balcarcel said she actually started putting her words on paper when she began to “capture the voice of bi-cultural tween. In my mind, I could hear her talking about her life. Next, I imagined incidents that would challenge her.”

Two years later, she said she had crafted about 25,000 words of vignettes or poems in Quijana’s voice. It took a lot of rewriting and the invention of new scenes, but in an additional two years, based on her agent’s recommendation, Barcarcel said she had connected the poems together, creating her first 60,000-word manuscript.

One of the greatest undertakings she had writing her book was ensuring that “the poetry in the book served the story,” said Balcarcel, whose master’s degree is in poetry.

“I trimmed back some of the sections and cut some parts entirely because novels need to move forward with every sentence. Once I got into the story-telling, my next challenge was to make time to sit and do the real typing. Don’t ask me about any TV show from the last five years. I haven’t seen it!”

The final obstacle blocking her from a finished book was the revision process. She said once something was suggested it was difficult for her to “un-see it,” as she tried to “find a way to make a broken thing work.”

What that meant in one situation was that she created new scenes for a character whose death originally occurred in chapter three. “Keeping that character alive meant creating scenes and dialogue and a character arc for her,” Barcarcel recalled, adding: “Whew! Writing is hard work.”

Despite the challenges of the creative process, Barcarcel already is on the sixth chapter of her next book, also a middle-grade novel with a bicultural main character. Her advice to budding writers is to read.

“When you read, you learn the tricks of language that authors use, and you absorb story-telling techniques. Read inside your genre and outside, too. Read, read, read,” she said.

“Then give yourself permission to write badly. Remember that all books start out as a mess. The writing process isn’t a straight line. It’s circular and recursive. It takes unexpected turns. Follow a few false trails to learn the lay of the land. It all contributes to the final version.”

The last recommendation she has for beginning writers is that it is important to listen to critique.

“Even if you don’t follow people’s suggestions, hear that they are confused or seeing something you didn’t intend. Fix it your own way, but don’t ignore it,” Barcarcel encouraged. “At the same time, stay true to the heart of your character or your idea. You may have to change the delivery, but the soul of your project should shine through.”