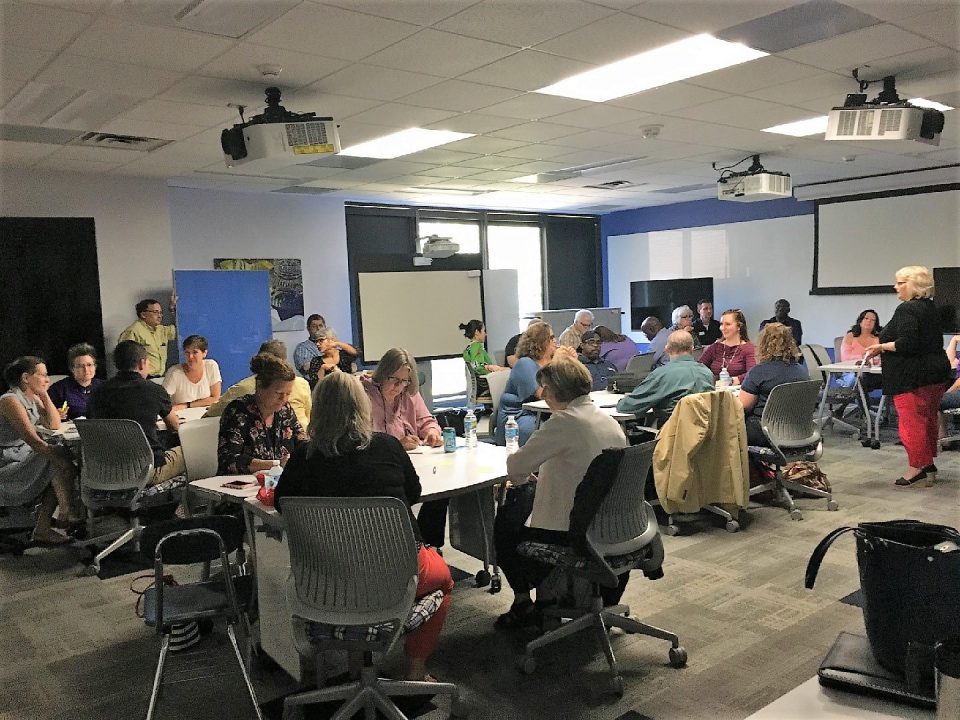

It is evident from first glimpse that NTAB 2203 is no ordinary classroom. Instead of one ceiling-mounted projector and screen, there are three, and they are your usual variety. A fourth projector is oddly shaped and its screen hangs vertically like an apron. There are four large flat screen television receivers, not wall-mounted, but completely mobile. The furniture is modular and can be arranged in endless configurations. There are monolith-looking glass panels – two white, one blue – and a touchscreen panel.

However, only when Caroline Hamilton, Ph.D., explains how the equipment functions, how it can literally bring new dimensions to learning and how the technology yet to be deployed that one realizes just how extraordinary the new experiential classroom is.

The classroom is the creative output of Hamilton, NE President Allen Goben, retired Media Services Director David Mead and Director of Campus Support Services Cedric Hights. They did not start with list of what the classroom would contain, but by listing what they wanted the classroom to be. First, Hamilton said it would be a “more transformative learning environment,” that students would be more immersed in and by the technology and thus would learn and retain more. “It’s the cool factor,” she said. “They walk in and are just in awe of what the space is.”

Second, the space will use technology to merge credit and non-credit programs in the future and open the door to new credentials in STEM-related fields.

Third, and dear to the heart of Hamilton, campus coordinator for professional development, the room will be a hub for training faculty and staff to be able to extend the knowledge and uses of technology in classrooms, labs and workspaces.

“People love it,” Hamilton said. “They want to use it. People are bringing their classes in that are not necessarily registered for the space.”

The classroom made its debut in the second eight-week term of the spring semester with a Dance Appreciation class taught by Dean Linda Quinn. “What happened in that space was absolutely amazing,” Hamilton said, “the retention and success she had with her students.”

The classroom made its debut in the second eight-week term of the spring semester with a Dance Appreciation class taught by Dean Linda Quinn. “What happened in that space was absolutely amazing,” Hamilton said, “the retention and success she had with her students.”

Courses this fall include microbiology, history, government, theater and speech, and the rush began in September to sign up for the spring. Hamilton said she would love to accommodate all the requests, but there are only so many hours in a day. Furthermore, she is trying to keep a balance among courses in all divisions.

What both students and faculty seem to appreciate most is the classroom’s flexibility. “There’s no hierarchy in there,” Hamilton said. “They can move all over the place and it gives them a chance to think, to ponder, to wonder and to work collaboratively in groups.”

That is where technology comes in. Instead of one projector sending an image to one screen, the four projectors – and they are HD and 3-D – can send the same image or four different images. An instructor thus might augment a lecture by having a PowerPoint on one screen, video on another, notes on a third and still photos on a fourth.

That odd projector out has a special capability. It is a “short throw” projector that can show images on its vertical screen, but that screen can flip horizontally to function as what Hamilton calls a “dynamic table” on which students can draw. Their work can be captured and saved by the instructor and sent to all screens so that other students can see it.

Moreover, those television receivers have a computer hookup so that groups of students can be paired with each one. Therefore, it is possible for four groups of students to watch separate videos, taking in the audio through earbuds.

The faculty might love it, but they have a price to pay. The classroom is a research facility, and instructors to report to Hamilton on what uses the equipment was put to and the extent to which it appears to be changing the way students retain the information. The hardware is cool, but can one learn on it?

“Not just can you learn on it,” Hamilton said, “but can you retrieve that information and can you apply that information, and can we create a learning space that helps to represent all of that at one time? I think we’re on a path to that.”

Impressive as all this is, the best is yet to come. Stacked in a storage room next to the experiential classroom are 20 small black cartons. Each contains a Microsoft Hololens, a wearable computer with which one can tour Rome, the solar system, the human body or whatever can be programmed.

The Hololens fits around the head with a semi-transparent screen over the eyes. It is not a virtual reality, but an augmented reality. The wearer is there (wherever that is), but also here able to see the real environment.

Once made available for use, the Hololens will enable instructors to take students on guided tours of wherever their imaginations and the course syllabi lead. The image on the screen can be manipulated, using a finger as the mouse. If St. Peter’s in Rome is the subject, the viewer can move all round it and zoom in to capture details.

Nevertheless, there is nothing virtual or augmented about the excitement Hamilton exudes when talking about the experiential classroom. “It’s exciting for people,” she said. “They hear more and more about it and they say, ‘It’s just amazing that we have this on our campus.’ And I say, ‘Yes! And you need to use it.’”